| Vendor | |

|---|---|

|

Liepman Literary Agency

Marc Koralnik |

| Original language | |

| English | |

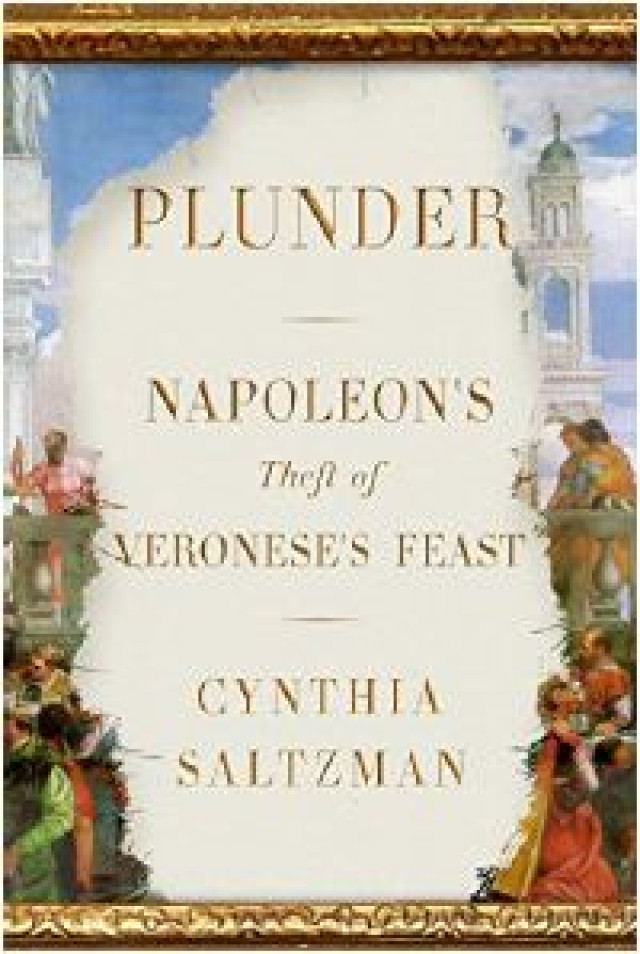

PLUNDER

Napoleon's Theft of Veronese's Feast

A captivating in-depth study of Napoleon's plundering of Europe's art and how it legitimized the Louvre.

Vast and sublime, more than twenty-two feet tall and thirty-two feet wide, and featuring a brilliantly staged, lavishly colored banquet with some hundred and thirty figures, Paolo Veronese's painting Wedding Feast at Cana was hailed as a masterpiece of High Renaissance art upon its completion in 1563. It hung in the monastery of the Venetian island of San Giorgio Maggiore until French troops, on the order of their twenty-eight-year-old leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, tore it off the wall of the monastery in 1797. Veronese's masterwork was one of twenty paintings that Napoleon took after his troops marched on Venice. Folded like a rug, the canvas ended up at the Louvre, establishing it as the greatest art museum in the world.

In Plunder: Napoleon's Theft of Veronese's Feast, the celebrated art historian Cynthia Saltzman tells the story of Napoleon's art looting and its relationship to the foundation of the Louvre. As Saltzman shows, Napoleon looted art for the French nation he represented; he displayed it in a public museum, which, owing to the plundered masterworks, soon became the toast of Europe. Napoleon's penchant for looting reflected the best and worst of his character: his desire for greatnessto carry forward the finest parts of civilizationand his ruthlessness in mythologizing himself and seizing power.

Expertly researched, and with rare insight into one of history's most famous and polarizing individuals, Plunder is a propulsive chronicle of the Napoleonic Wars, art theft, and the controversial origins of the world's greatest museum.

CYNTHIA SALTZMAN is the author of OLD MASTERS, NEW WORLD: AMERICA'S RAID ON EUROPE'S GREAT PICTURES and PORTRAIT OF DR. GACHET: THE STORY OF A VAN GOGH MASTERPIECE. The recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, she selected the letters and wrote an introduction for Vincent van Gogh Lettere, published by Einaudi in its I Millenni series.

Her work has focused on art in the late 19th centuryin Europe and Americaits creation, acquisition, and migrationits interplay with the economics, politics, and cultural ambitions of that time.

She holds a BA from Harvard University in Fine Arts, an MA from the University of California, at Berkeley, in the History of Art (1975), and an MBA from Stanford University (1977). She lives in New York.

In Plunder: Napoleon's Theft of Veronese's Feast, the celebrated art historian Cynthia Saltzman tells the story of Napoleon's art looting and its relationship to the foundation of the Louvre. As Saltzman shows, Napoleon looted art for the French nation he represented; he displayed it in a public museum, which, owing to the plundered masterworks, soon became the toast of Europe. Napoleon's penchant for looting reflected the best and worst of his character: his desire for greatnessto carry forward the finest parts of civilizationand his ruthlessness in mythologizing himself and seizing power.

Expertly researched, and with rare insight into one of history's most famous and polarizing individuals, Plunder is a propulsive chronicle of the Napoleonic Wars, art theft, and the controversial origins of the world's greatest museum.

CYNTHIA SALTZMAN is the author of OLD MASTERS, NEW WORLD: AMERICA'S RAID ON EUROPE'S GREAT PICTURES and PORTRAIT OF DR. GACHET: THE STORY OF A VAN GOGH MASTERPIECE. The recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, she selected the letters and wrote an introduction for Vincent van Gogh Lettere, published by Einaudi in its I Millenni series.

Her work has focused on art in the late 19th centuryin Europe and Americaits creation, acquisition, and migrationits interplay with the economics, politics, and cultural ambitions of that time.

She holds a BA from Harvard University in Fine Arts, an MA from the University of California, at Berkeley, in the History of Art (1975), and an MBA from Stanford University (1977). She lives in New York.

| Available products |

|---|

|

Book

Published 2021-03-01 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux |