| Vendor | |

|---|---|

|

Mohrbooks Literary Agency

Sebastian Ritscher |

| Original language | |

| English | |

| Categories | |

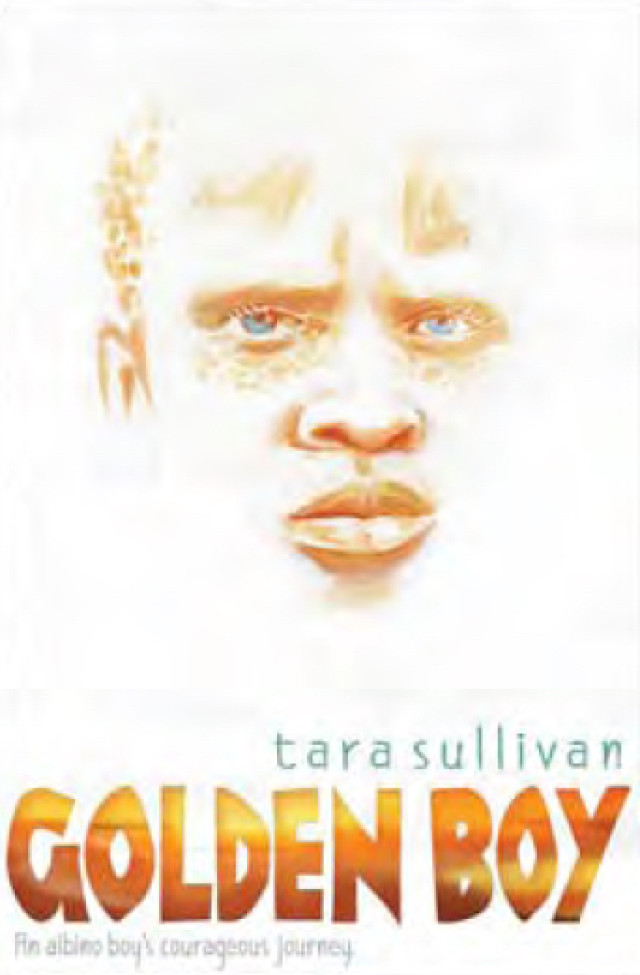

GOLDEN BOY

Thirteen year old Habo has always been different: Light eyes, yellow hair and white skin. Not the good brown skin his family has and not the white skin of tourists. When Habo and his family are forced to flee from their small village, they seek refuge in Mwanza. His aunt is glad to open her home until she sees Habo for the first time, and then she is only afraid. Suddenly, Habo has a new word for himself: Albino. They hunt Albinos in Mwanza because Albino body parts are thought to bring good luck. And soon Habo is being hunted. To survive Habo must not only run, but he must also find a way to love and accept himself.

Habo has never fit in - not in his family, not in his Tanzanian village, and certainly not in Mwanza, the city to which his family has had to relocate due to their poverty. In Mwanza, there are poachers who hunt albinos like him and kill them in order to sell their body parts to those who believe that they will bring good fortune--and one of them is Alasari, the poacher who helped Habo's family travel across the Serengeti. Like the elephant that Alasari killed for its ivory, Habo is valued only for the parts that can be sold, and Alasari will stop at nothing to kill Habo and collect his bounty.

Habo flees to the capital of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam, where he meets Kweli, a blind sculptor who cannot see how an albino boy is different from any other. The old man’s affection, coupled with his own disgust at the objectification that turned him into a commodity, prompt Habo to reject the idea that he is less than human for the first time in his life. Under Kweli’s tutelage, Habo discovers self-expression through the art of makonde carving, eventually earning enough money to reunite his family.

Tara Sullivan was born in Calcutta and spent her childhood and early adolescence moving around South America and the Caribbean with her parents who were international aid workers. Not only did this mean that many dinner table conversations centered on issues of international justice and poverty alleviation, but it was awkwardly normal for her to be the only white kid in the market, at the birthday party, or on the bus. Though she spoke Spanish like a native and felt more comfortable in Bolivia than holding her American passport, she was always seen as the outsider. When the UV rays from the hole in the ozone over the Andes damaged her eyes beyond repair, her family was forced to leave what had always felt like home and move to America. Two years ago, when she came across a news story that told about the kidnapping, mutilation, and murder of African albinos for use as good luck talismans, Tara was struck by the topic on multiple levels. The grown-up in Tara, the one that studied for a dual Masters in Non-Profit Management and International Studies and worked with village micro-finance and refugee resettlement programs, wanted to publicize this human rights tragedy. The kid in her, the one who had to hide from the sun and could never blend into a crowd, wanted to tell a story about what it must feel like to be a kid who has those problems in the extreme. In Golden Boy she hopes to do both.

Habo flees to the capital of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam, where he meets Kweli, a blind sculptor who cannot see how an albino boy is different from any other. The old man’s affection, coupled with his own disgust at the objectification that turned him into a commodity, prompt Habo to reject the idea that he is less than human for the first time in his life. Under Kweli’s tutelage, Habo discovers self-expression through the art of makonde carving, eventually earning enough money to reunite his family.

Tara Sullivan was born in Calcutta and spent her childhood and early adolescence moving around South America and the Caribbean with her parents who were international aid workers. Not only did this mean that many dinner table conversations centered on issues of international justice and poverty alleviation, but it was awkwardly normal for her to be the only white kid in the market, at the birthday party, or on the bus. Though she spoke Spanish like a native and felt more comfortable in Bolivia than holding her American passport, she was always seen as the outsider. When the UV rays from the hole in the ozone over the Andes damaged her eyes beyond repair, her family was forced to leave what had always felt like home and move to America. Two years ago, when she came across a news story that told about the kidnapping, mutilation, and murder of African albinos for use as good luck talismans, Tara was struck by the topic on multiple levels. The grown-up in Tara, the one that studied for a dual Masters in Non-Profit Management and International Studies and worked with village micro-finance and refugee resettlement programs, wanted to publicize this human rights tragedy. The kid in her, the one who had to hide from the sun and could never blend into a crowd, wanted to tell a story about what it must feel like to be a kid who has those problems in the extreme. In Golden Boy she hopes to do both.

| Available products |

|---|

|

Book

Published 2013-06-01 by G.P. Putnam's Sons |

|

Book

Published 2013-06-01 by G.P. Putnam's Sons |