| Vendor | |

|---|---|

|

Mohrbooks Literary Agency

Sebastian Ritscher |

| Original language | |

| English | |

| Categories | |

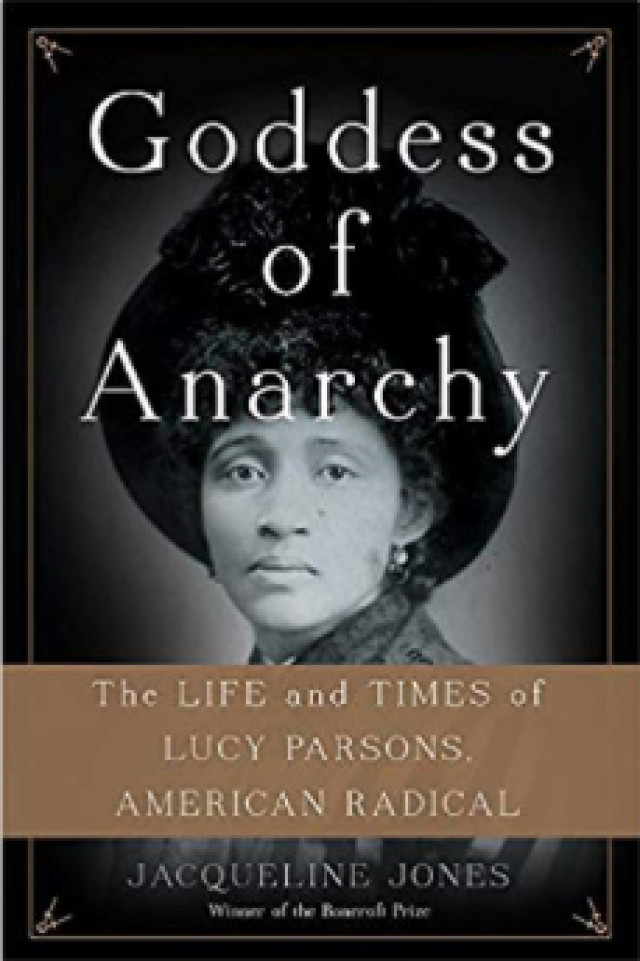

GODDESS OF ANARCHY

The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical

From a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist historian, a new portrait of an extraordinary activist and the turbulent age in which she lived.

Goddess of Anarchy is the biography of the formidable radical activist, writer, and orator Lucy Parsons (1853-1942), also known as Lucia Eldine Gonzalez Parsons, whose long life was entwined with the major radical labor struggles of her turbulent era. Born to an enslaved woman in Virginia in 1851, Parsons became the wife of Confederate veteran and anarchist organizer Albert R. Parsons, who was unjustly imprisoned and eventually hanged in 1887 for his alleged role in the Haymarket bombing in Chicago.

After Albert's imprisonment and death, Parsons forged her own career as orator and labor agitator, editor, free-speech activist, essayist, fiction writer, publisher, and political commentator. A fearless advocate of First Amendment rights, a founding member of the Socialist Party of America in 1900, and a cofounder of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, Parsons was one of only a handful of women and the only African American of her era to speak regularly to large crowds throughout the nation. Parsons was a thoughtful critic of Gilded Age America, but also well-known for her rhetorical provocations, urging the laboring classes to "learn the use of explosives" to protect themselves from predatory industrialists and police forces. She worked closely with, or bitterly against, other labor agitators of her day, including Eugene Debs and Emma Goldman, with whom she had a feud about the sexual liberation of women; Parsons considered Goldman's emphasis on birth control and "free love" to be a distraction from the bigger fight against the "wage slavery" of the lower classes.

And yet Lucy Parsons' life was shrouded contradictions, marked by a series of traumas and personal tragedies. Surrounding herself with an aura of mystery, she presented herself as a champion of the laboring classes, settled in a neighborhood of German immigrants, and ignored the plight of African Americans. She concocted a false identity for herself, claiming to be the daughter of Mexican and Indian parents, in an effort to deny her African heritage. In public, she presented herself as an upholder of conventional sexual morality, when in fact she took several lovers after her husband's death. Also, she committed her 19-year old son Albert, Jr. to a mental institution, which continues to generate controversy over who she was, as a labor-organizer but also a mother.

Jacqueline Jones holds the Ellen C. Temple Chair in Women's History and the Mastin Gentry White Professorship in Southern History at the University of Texas at Austin. Winner of the Bancroft Prize for Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow, Jones lives in Austin, Texas.

After Albert's imprisonment and death, Parsons forged her own career as orator and labor agitator, editor, free-speech activist, essayist, fiction writer, publisher, and political commentator. A fearless advocate of First Amendment rights, a founding member of the Socialist Party of America in 1900, and a cofounder of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, Parsons was one of only a handful of women and the only African American of her era to speak regularly to large crowds throughout the nation. Parsons was a thoughtful critic of Gilded Age America, but also well-known for her rhetorical provocations, urging the laboring classes to "learn the use of explosives" to protect themselves from predatory industrialists and police forces. She worked closely with, or bitterly against, other labor agitators of her day, including Eugene Debs and Emma Goldman, with whom she had a feud about the sexual liberation of women; Parsons considered Goldman's emphasis on birth control and "free love" to be a distraction from the bigger fight against the "wage slavery" of the lower classes.

And yet Lucy Parsons' life was shrouded contradictions, marked by a series of traumas and personal tragedies. Surrounding herself with an aura of mystery, she presented herself as a champion of the laboring classes, settled in a neighborhood of German immigrants, and ignored the plight of African Americans. She concocted a false identity for herself, claiming to be the daughter of Mexican and Indian parents, in an effort to deny her African heritage. In public, she presented herself as an upholder of conventional sexual morality, when in fact she took several lovers after her husband's death. Also, she committed her 19-year old son Albert, Jr. to a mental institution, which continues to generate controversy over who she was, as a labor-organizer but also a mother.

Jacqueline Jones holds the Ellen C. Temple Chair in Women's History and the Mastin Gentry White Professorship in Southern History at the University of Texas at Austin. Winner of the Bancroft Prize for Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow, Jones lives in Austin, Texas.

| Available products |

|---|

|

Book

Published 2017-12-05 by Basic Books |